It’s 2025, and you’re picking up your monthly prescription for generic levothyroxine. Last month, it was $5. This month? $45. You didn’t change anything. Your doctor says all generics are the same. So why did the price jump?

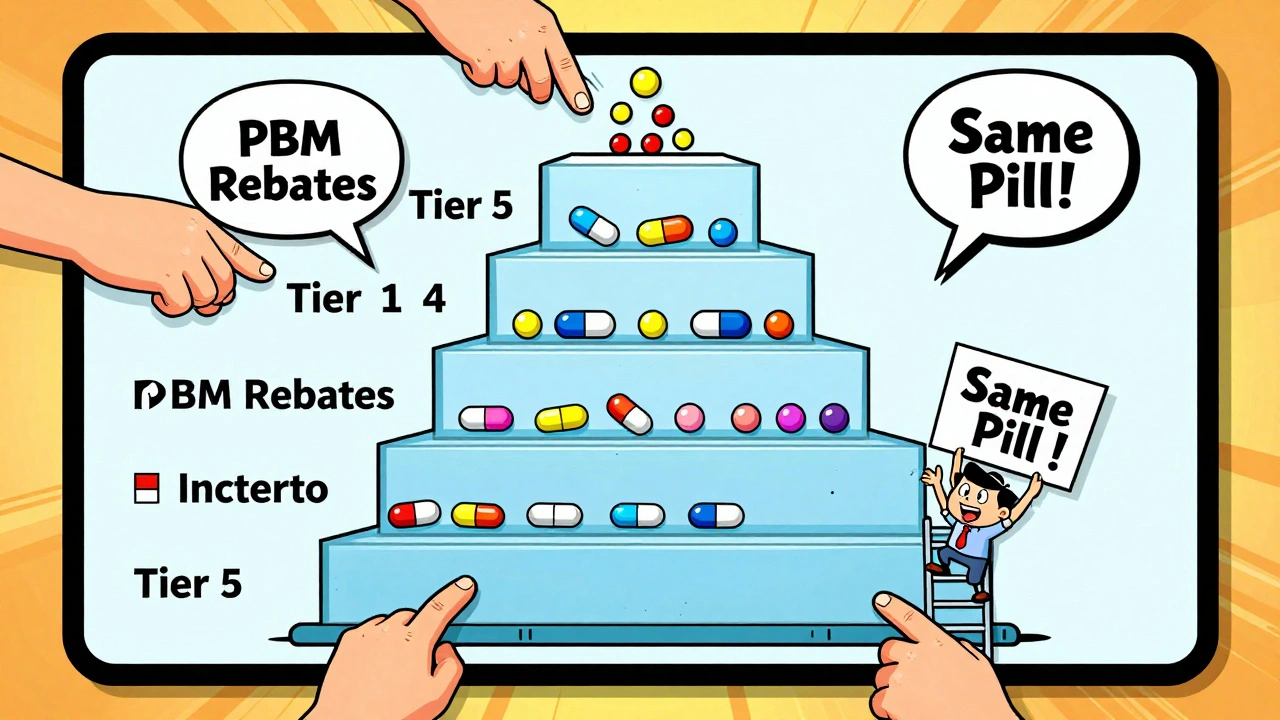

You’re not alone. Thousands of people get the same shock every year. The culprit? Tiered copays. Most health plans don’t charge one flat fee for all prescriptions anymore. Instead, they sort drugs into tiers - like levels in a video game - and each tier has a different price tag. The problem? Not all generics are treated equally. Some cost more, even though they’re chemically identical to cheaper ones.

How Tiered Copays Actually Work

Tiered copays split your prescriptions into groups, usually four or five levels. The idea is simple: encourage you to pick cheaper drugs by making them cheaper to buy. Tier 1 is for the lowest-cost generics. Tier 2 is for preferred brand-name drugs. Tier 3 is for non-preferred brands. Tiers 4 and 5 are for expensive specialty drugs.

Here’s how it breaks down in real dollars (based on 2024 plan data):

- Tier 1: Preferred generics - $0 to $15 for a 30-day supply

- Tier 2: Preferred brands or non-preferred generics - $25 to $50

- Tier 3: Non-preferred brands - $60 to $100

- Tier 4: Preferred specialty drugs - 20% to 25% coinsurance

- Tier 5: Non-preferred specialty drugs - 30% to 40% coinsurance

At first glance, this seems fair. But here’s the catch: your generic drug might not be in Tier 1 - even if it’s the exact same pill as the one that cost $5 last month.

Why Your Generic Is in a Higher Tier

It’s not about effectiveness. It’s not about safety. It’s not even about how many people take it.

It’s about money - specifically, the rebate deals between your insurer’s pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) and drug manufacturers.

Let’s say two companies make generic atorvastatin (the cholesterol drug). One gives the PBM a big rebate - say, $10 per pill. The other gives nothing. Even though both pills are identical, the one with the rebate lands in Tier 1. The other? Tier 2. Your copay jumps from $5 to $15. You didn’t ask for this switch. Your doctor didn’t recommend it. But your pharmacy automatically fills it with the cheaper option for the insurer - not for you.

According to industry data from Avalere Health, 68% of generic drugs moved to higher tiers in 2023 were due to expired rebate contracts - not clinical reasons. That means your drug got bumped up because the manufacturer stopped paying the PBM enough money to keep it in the lowest tier.

And it’s not rare. About 12% to 18% of all generic medications in major plans are stuck in Tier 4 or 5 - the same tier as cancer drugs and biologics - because they’re used for rare conditions or require special handling. A generic version of adalimumab (used for rheumatoid arthritis) might cost $5,000 a month. Even though it’s a generic, you pay 30% coinsurance. That’s $1,500 out of pocket. No one tells you this until you get the bill.

The Confusion Is Real

Patients are confused. A 2023 survey by the Patient Advocate Foundation found that 41% of insured adults had experienced a generic drug suddenly costing more - and 68% couldn’t get a clear answer from their insurer.

On Reddit, users post things like: “My levothyroxine went from $5 to $45. My doctor says it’s the same. Why is my insurance doing this?”

Pharmacists are caught in the middle. They’re trained to substitute generics to save money - but sometimes, the substitute is the more expensive one for you. They may switch your prescription without asking, assuming you’ll be fine with the new copay. You don’t know until you pay.

And when you ask why, you get robotic answers: “It’s based on our formulary.” “That’s the tier it’s on.” No explanation. No options.

What You Can Do About It

You don’t have to accept this. Here’s what actually works:

- Check your formulary every year. Plans update them on October 1. Log into your insurer’s website. Look up your drug by name. See what tier it’s on. If it changed, note it.

- Ask your pharmacist for alternatives. Say: “Is there another generic version of this drug that’s cheaper?” Often, there is - and it’s in Tier 1. Pharmacists can usually switch it without calling your doctor.

- Request a therapeutic interchange. If your doctor agrees, they can submit a form asking your plan to cover your preferred generic at the lower tier. Success rate? Around 63%.

- Use cost tools. GoodRx, SmithRx, and your insurer’s drug lookup tool show real-time copays across pharmacies. You might save $50 a month just by switching where you pick up your script.

- Appeal if needed. If your drug was moved to a higher tier mid-year, you can file an exception. Urgent cases (like insulin or heart meds) can be approved in 72 hours.

- Check manufacturer programs. Many drugmakers offer coupons or patient assistance. In 2023, these programs covered 22% of specialty drug costs for eligible patients.

Don’t wait for your next refill. Do this now. A simple search can save you hundreds a year.

Why This System Still Exists

Insurers and PBMs say tiered copays control costs. And they’re right - studies show these systems cut overall drug spending by 8% to 12%. But the savings don’t always reach you.

The real winners are the PBMs. They collect rebates from manufacturers, and those rebates are how they make money. The higher the tier, the more leverage they have to demand discounts. Your higher copay? That’s part of the deal.

Some experts, like Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard, call this practice “unfair.” He argues that if two drugs are clinically identical, they should cost the same - no matter what rebate deal was signed behind closed doors.

And change is coming. Starting in 2025, Medicare Part D will cap out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 a year. That’s good news. But it doesn’t change how tiers work. Your generic might still cost $45 - you’ll just hit the cap faster.

Some states are pushing laws to ban tiering of identical generics. So far, only a few have passed them. Until then, the system stays.

What’s Next for Tiered Copays

By 2026, most plans will shrink from five tiers to four. Specialty drugs will still be expensive. But more generics will be grouped into “value tiers” - where the most popular ones (like lisinopril or metformin) go to $0 copays. Less common generics? They’ll get pushed up.

And now, biosimilars - generic versions of biologic drugs - are entering the mix. These are complex, expensive, and insurers are already setting up tier systems for them. You’ll see even more confusion.

The bottom line? Tiered copays aren’t going away. But you don’t have to be powerless in them.

Know your plan. Ask questions. Shop around. Push back. That $45 generic isn’t a mistake - but it’s not a rule either. It’s a negotiation you can join.

Why is my generic drug more expensive than the brand-name version?

It’s rare, but it happens. This usually means your brand-name drug is on a lower tier because the manufacturer pays a large rebate to your insurer’s pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). Meanwhile, your generic - even if chemically identical - is on a higher tier because its maker didn’t offer a big enough discount. The system rewards rebates, not clinical value.

Can my pharmacist switch me to a cheaper generic without asking?

Yes, and they often do. Pharmacists are allowed to substitute generics unless your doctor writes “dispense as written” on the prescription. But they usually pick the one with the lowest cost to the insurer - not necessarily the cheapest for you. Always ask: “Is this the lowest-cost generic for my plan?”

How often do insurance plans change drug tiers?

Plans update their formularies once a year, usually on October 1. But 17% of commercial plans made changes between January and June 2023, according to CMS data. If your drug’s price suddenly jumps mid-year, it’s likely due to a rebate contract ending - not a clinical decision.

What’s the difference between a preferred and non-preferred generic?

None, clinically. Both contain the same active ingredient, dosage, and effectiveness. The difference is purely financial: preferred generics are those whose manufacturers pay the highest rebates to your insurer’s pharmacy benefit manager. Non-preferred generics didn’t negotiate a good deal - so you pay more.

Can I appeal a tier change for my medication?

Yes. You can file an exception request with your insurer. You’ll need a letter from your doctor explaining why you need the specific generic - especially if you’ve had side effects or poor results with the substituted version. For urgent cases like heart or diabetes meds, approvals can happen in as little as 72 hours.

Are there tools to compare drug costs across plans?

Yes. GoodRx, SmithRx, and your insurer’s own drug lookup tool let you compare copays at different pharmacies and under different tiers. Some even show which generics are preferred in your plan. Use them before filling any prescription - you could save $30 to $150 a month.

George Taylor

So let me get this right... I pay $45 for a pill that’s chemically identical to the one that cost $5... and the only reason? Some corporate middleman got a kickback? That’s not healthcare-that’s extortion with a pharmacy label. I’m not even mad, I’m just... done. 🤡

Carina M

It is, indeed, a matter of profound ethical concern that the pharmaceutical benefit management industry has systematically subordinated patient welfare to profit-driven rebate architectures. The commodification of therapeutic equivalence-where clinical indistinguishability is rendered irrelevant by contractual pecuniary arrangements-constitutes a systemic failure of fiduciary duty in public health policy.

Ajit Kumar Singh

Bro this is why India has generic drugs at 10 rupees you guys are getting robbed every single time and no one does anything. I mean seriously? You have insurance and still paying 45 for levothyroxine? In Delhi you get it for 20 rupees with delivery. America is broken

Maria Elisha

Ugh I just got hit with this last month. Same script. Same doctor. Same pharmacy. Suddenly $40? I thought I was going crazy. Called my insurer, got a robot. Called my pharmacist, they shrugged. So I just started buying it on GoodRx now. $7. It’s wild.

Angela R. Cartes

Okay but like… why are we still pretending this is a medical system? 😩 It’s a casino. The house always wins. I just got my insulin tier changed to Tier 5 last week. I’m 32. I shouldn’t be choosing between rent and my meds. 🤦♀️

Sabrina Thurn

It’s critical to understand that tiering is not a clinical tool-it’s a financial lever wielded by PBMs. The term ‘preferred generic’ is a misnomer; it should be labeled ‘rebate-optimized generic.’ The FDA considers generics therapeutically equivalent, yet payers create artificial distinctions that directly impact patient adherence. This is a policy failure, not a market inefficiency. Patients need transparency: real-time tier data, rebate disclosures, and mandatory formulary change notifications 90 days in advance. Without structural reform, this will continue to erode trust in the entire system.

Courtney Black

There’s a silence here. A quiet violence. We don’t talk about how the body becomes a ledger. How a thyroid pill becomes a transaction. How the same molecule, the same science, the same biology-can be priced like a luxury good because someone signed a contract in a room where no patient was ever invited. We call it healthcare. But it’s not. It’s a marketplace that turned your survival into a commodity. And we’re supposed to be grateful for the discount?

iswarya bala

this is so true!! i live in india and we get generic medecine for like 10rs but here in usa ppl are getting ripped off. i just told my cousin to get her meds from india through a friend. she saved 90%!! its crazy how broken the system is

Simran Chettiar

The fundamental issue lies not in the tiered structure per se, but in the opacity and arbitrariness of its application. When therapeutic equivalence is rendered meaningless by commercial negotiations conducted behind closed doors, the very concept of patient autonomy is undermined. The patient, in this paradigm, is not a participant but a passive recipient of corporate calculus. This is not innovation; it is institutionalized exploitation cloaked in the language of cost containment. Until we decouple pricing from rebate incentives and enforce true therapeutic parity, we are not healing-we are profiting from illness.

Anna Roh

Same thing happened to my metformin. Went from $3 to $35. Called my doctor. He said ‘just switch to the other generic.’ I did. Same pill. Different box. Different price. I swear I’m gonna start buying my meds at Costco. They don’t even use the same PBMs.

om guru

The system is designed to exploit. But you are not powerless. Knowledge is your tool. Ask your pharmacist. Use GoodRx. Check formulary. File exception. You are not a number. You are a human being deserving of affordable care. Take action. One step at a time.

Philippa Barraclough

It’s fascinating-and deeply troubling-how the structural incentives within the PBM model create perverse outcomes that directly contradict the stated goals of cost containment. If the objective is to reduce overall expenditures, then the fact that rebates are extracted from manufacturers and retained by PBMs, while patients bear the brunt of higher copays, suggests a misalignment between policy rhetoric and economic reality. The absence of transparency around rebate flows means patients are effectively subsidizing corporate profits under the guise of ‘lower premiums.’ This isn’t just broken-it’s engineered.