Vasculitis isn't one disease-it's a group of rare autoimmune disorders where the body's immune system turns against its own blood vessels. Instead of protecting you, it attacks the walls of arteries, veins, and capillaries, causing inflammation, narrowing, blockages, or even ruptures. This can starve organs of oxygen and nutrients, leading to serious damage-or death-if not caught early. It doesn't discriminate by age, but who gets it and how it behaves depends heavily on which vessels are targeted and how aggressively the immune system responds.

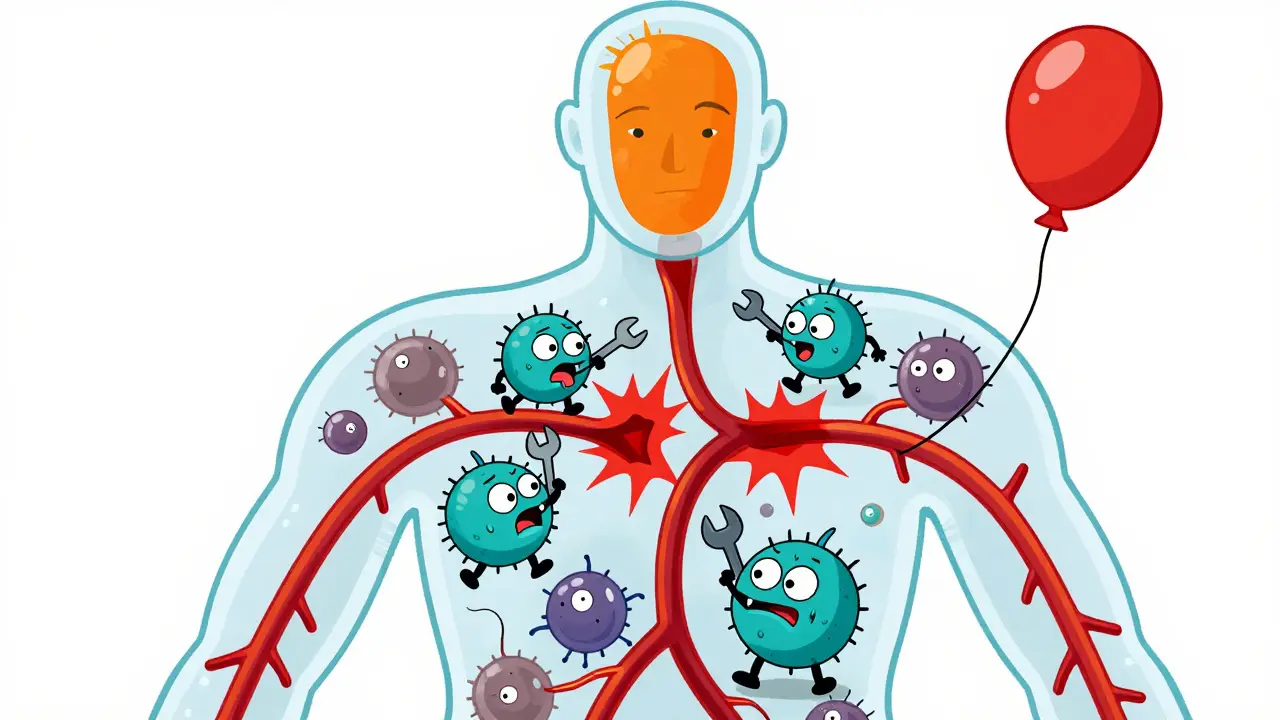

How Vasculitis Attacks Your Blood Vessels

Your blood vessels are the highways of your body, carrying oxygen and nutrients to every organ. When vasculitis strikes, the immune system sends inflammatory cells straight into the vessel walls. These cells don't just swell the area-they chew through layers of tissue. In the early stages, neutrophils swarm in, releasing enzymes that break down proteins. Later, lymphocytes take over, turning the inflammation chronic. The result? Thickened walls, scar tissue, narrowed passages, or worse-weak spots that balloon into aneurysms.It can happen anywhere. A small vessel in your skin might show up as purple spots or ulcers. A medium vessel in your kidneys can cause silent kidney failure. A large vessel like the aorta or temporal artery can lead to stroke, vision loss, or heart attack. The damage isn't always obvious until it's advanced. That’s why many people go months or even years without a diagnosis-symptoms like fatigue, joint pain, or fever get written off as the flu or aging.

Types of Vasculitis: Size Matters

Doctors classify vasculitis by the size of the blood vessels it targets. This isn't just academic-it guides treatment and predicts outcomes.- Large-vessel vasculitis affects the aorta and its biggest branches. Giant cell arteritis (GCA) hits people over 50, often starting with severe headaches, jaw pain when chewing, or sudden vision loss. Takayasu arteritis mostly affects young women and can cause weak pulses in the arms or high blood pressure from narrowed arteries.

- Medium-vessel vasculitis targets arteries feeding muscles and organs. Polyarteritis nodosa can damage kidneys, nerves, and the gut, causing abdominal pain, numbness, or high blood pressure. Kawasaki disease, seen mostly in kids under 5, inflames coronary arteries-up to 25% of untreated children develop dangerous aneurysms.

- Small-vessel vasculitis is the most common and often the most dangerous. This group includes granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). These are often linked to ANCA antibodies, which attack white blood cells and trigger vessel inflammation. GPA can cause sinus infections, lung nodules, and kidney failure. MPA hits kidneys and lungs hard. EGPA adds asthma and high eosinophil counts to the mix.

Then there’s Buerger’s disease, tied tightly to smoking. It clogs small arteries and veins in hands and feet, leading to painful ulcers and even amputation. Quitting tobacco isn’t optional-it’s the only treatment that works.

Diagnosis: Finding the Invisible Enemy

There’s no single blood test for vasculitis. Diagnosis is a puzzle made of symptoms, lab work, imaging, and biopsy.Doctors start with basic blood tests. If your ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) is over 50 mm/hr or your CRP (C-reactive protein) is above 5 mg/dL, inflammation is likely. But that’s not enough. The real clue often comes from ANCA testing. c-ANCA (targeting proteinase-3) is 80-90% specific for GPA. p-ANCA (targeting myeloperoxidase) points to MPA or EGPA. But even these aren’t perfect-some healthy people have low levels, and some patients with confirmed vasculitis test negative.

Imaging helps map the damage. Ultrasound can show thickened temporal arteries in GCA. CT or MRI scans reveal aneurysms or blockages in larger vessels. PET scans are becoming more common to spot active inflammation in arteries that aren’t easily biopsied.

But the gold standard? Tissue biopsy. A sample from an affected area-skin, kidney, lung, or temporal artery-can show the telltale signs: immune cells inside vessel walls, fibrinoid necrosis, or leukocytoclastic debris. For skin vasculitis, a biopsy often confirms the diagnosis when rashes look suspicious. For kidney involvement, a renal biopsy is critical to determine if treatment needs to be aggressive.

Treatment: Turning Off the Immune Attack

Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. It depends on the type, severity, and which organs are at risk.For severe cases, the goal is rapid control. That usually means high-dose prednisone (0.5-1 mg per kg daily) to crush inflammation fast. But steroids alone aren’t enough-they cause bone loss, diabetes, weight gain, and mood swings. So they’re paired with stronger drugs:

- Cyclophosphamide has been the go-to for decades. It’s powerful but can cause bladder damage and infertility.

- Rituximab targets B-cells, the immune cells that make harmful antibodies. It’s now preferred for many patients because it’s just as effective with fewer long-term risks.

Once remission is reached (often within 3-6 months), doctors switch to maintenance therapy. This lasts 18-24 months or longer to prevent relapse. Options include azathioprine, methotrexate, or continued rituximab infusions every 6 months.

Recent breakthroughs are changing the game. Avacopan, approved by the FDA in 2021, blocks a key inflammation signal (C5a). In the ADVOCATE trial, patients on avacopan plus low-dose steroids had the same remission rates as those on high-dose steroids-but with 2,000 mg less cumulative steroid exposure over a year. That means fewer side effects, faster recovery.

For giant cell arteritis, tocilizumab (an IL-6 inhibitor) is now approved as an add-on. It helps cut steroid doses in half and reduces relapse risk. For EGPA, mepolizumab (which targets eosinophils) has shown up to 50% fewer flares in trials.

Prognosis: Can You Live With It?

The good news? Most people with vasculitis can live full lives-if treated early. About 80-90% of those with ANCA-associated vasculitis reach remission. But the bad news? Half of them relapse within five years. That’s why lifelong monitoring is non-negotiable.Survival rates vary. For polyarteritis nodosa, if no major organs are involved, 95% survive five years. If kidneys or heart are damaged, that drops to 50-75%. Kidney failure, stroke, or lung hemorrhage are the biggest killers.

Children with Kawasaki disease need cardiac follow-up for life-even if they seem fine after treatment. Coronary aneurysms can form silently and rupture years later. Adults with GCA must watch for vision loss; it can happen in hours if the ophthalmic artery gets blocked.

What You Should Watch For

Symptoms vary wildly, but here are red flags that shouldn’t be ignored:- Purple or red spots, bumps, or bruises on legs that don’t fade

- Unexplained fever, fatigue, or weight loss for more than two weeks

- New headaches, jaw pain, or vision changes after age 50

- Coughing up blood or shortness of breath with no clear cause

- Abdominal pain, nausea, or bloody stools without a known GI condition

- Numbness, tingling, or weakness in hands or feet

- Severe asthma that started in adulthood, especially with sinus problems

If you have any of these and they won’t go away, don’t wait. See a rheumatologist. General practitioners often miss vasculitis because it mimics common illnesses. The average delay in diagnosis? 6 to 12 months.

Living With Vasculitis: Beyond Medication

Medication controls the disease-but lifestyle keeps you strong. Steroids weaken bones, so get enough calcium and vitamin D. Exercise helps maintain muscle and circulation, even if you’re tired. Avoid smoking completely-even secondhand smoke can trigger flares.Regular blood and urine tests are essential. Even if you feel fine, kidney damage can creep up silently. A simple urine dipstick can catch protein or blood before it’s too late.

Join a support group. Many patients feel isolated because vasculitis is so rare. Connecting with others who understand the fatigue, the fear of relapse, and the frustration of being misunderstood makes a huge difference.

Can vasculitis be cured?

There’s no permanent cure, but most people can achieve long-term remission with the right treatment. Many live normal lives for decades. The goal isn’t to eliminate the disease entirely-it’s to keep it suppressed so it doesn’t damage organs. Relapses happen, but they’re manageable with early detection.

Is vasculitis hereditary?

No, vasculitis isn’t directly inherited. But some people have genetic traits that make their immune systems more likely to overreact. If you have a close relative with an autoimmune disease like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, your risk may be slightly higher-but it’s still very low overall.

Can children get vasculitis?

Yes. Kawasaki disease is the most common type in kids under 5. It can cause coronary artery aneurysms if untreated. Other types, like polyarteritis nodosa or microscopic polyangiitis, can also occur in children but are much rarer. Pediatric cases require specialized care, including regular heart monitoring.

Do I need to avoid certain foods?

No specific diet cures vasculitis. But steroids can raise blood sugar and blood pressure, so it helps to eat less sugar, salt, and processed foods. Focus on whole grains, lean proteins, vegetables, and healthy fats. If you have kidney involvement, your doctor may recommend limiting protein or potassium.

Can I still work or exercise with vasculitis?

Yes, most people can. Fatigue is common, so pace yourself. Low-impact exercise like walking, swimming, or yoga helps maintain strength and circulation. If your job involves heavy lifting or long hours on your feet, talk to your doctor about accommodations. Many patients return to full-time work after remission.

What happens if I stop my medication?

Stopping treatment without medical supervision is dangerous. Even if you feel fine, the inflammation may still be active under the surface. Stopping steroids too fast can trigger a rebound flare. Stopping immunosuppressants can lead to organ damage within weeks. Always taper medications under your rheumatologist’s guidance.

caroline hernandez

ANCA-associated vasculitis is such a complex beast - the c-ANCA/p-ANCA distinction isn't just academic, it's clinically pivotal. I've seen patients misdiagnosed for years because their p-ANCA was low-titer and they didn't have classic renal involvement. The key is integrating serology with biopsy findings and clinical context. And don't get me started on how underutilized PET-CT is for detecting subclinical vascular inflammation - it's a game-changer for monitoring treatment response without invasive procedures.

Avacopan is revolutionary. Reducing steroid burden by 2000mg annually? That’s not just a win for bone density - it’s a win for mental health, metabolic stability, and quality of life. We’re finally moving beyond ‘steroids as default’ in autoimmune care.

Also, remember: not all vasculitis is ANCA-positive. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, IgG4-related disease, and even drug-induced forms can mimic ANCA vasculitis. Always rule out hepatitis, malignancy, and medications like propylthiouracil or hydralazine before committing to aggressive immunosuppression.