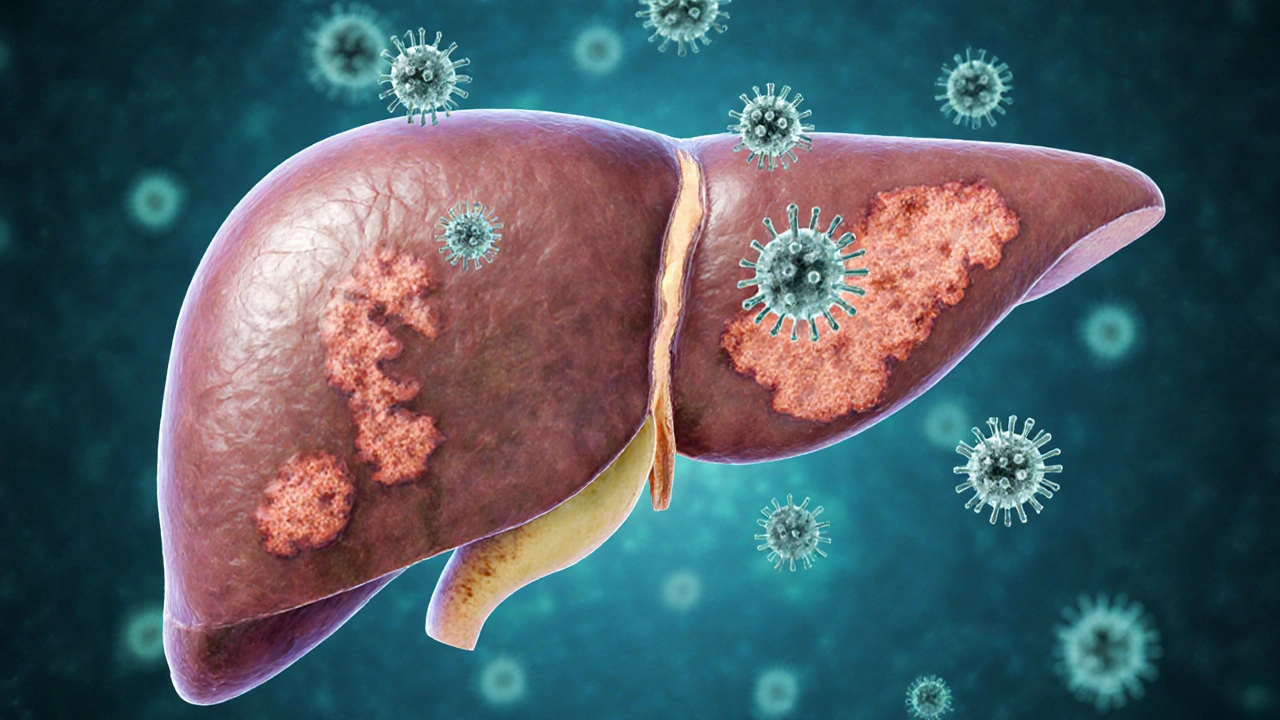

Chronic Hepatitis B is a long‑lasting liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) that can lead to serious liver damage, cirrhosis, and liver cancer.

What is Chronic Hepatitis B?

When the hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains in the body for more than six months, the infection is labeled chronic. Unlike the short‑term bout known as acute hepatitis B, the virus hides in liver cells and quietly replicates, often without obvious signs for years. According to the World Health Organization, more than 250million people worldwide live with chronic hepatitis B, making it a leading cause of liver‑related death.

Key Symptoms to Watch For

Because the virus can stay silent, many people discover they have chronic hepatitis B only after routine blood work. When symptoms do appear, they tend to develop slowly and may include:

- Persistent fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice).

- Dark urine and pale stools.

- Abdominal discomfort, especially in the right upper quadrant where the liver sits.

Lab tests often reveal elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, indicating liver inflammation. However, normal ALT doesn’t guarantee the virus isn’t harming the liver.

Root Causes and How the Virus Works

HBV is a DNA virus that targets liver cells (hepatocytes). Once it enters a cell, it forms a stable DNA form called covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), which acts like a hidden blueprint allowing the virus to persist. The body’s immune response decides whether the infection clears (acute) or lingers (chronic). Factors that tilt the balance toward chronicity include infection at a young age, a weak immune system, and certain viral genotypes.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Risk factors fall into three broad groups: exposure routes, demographic variables, and health‑related conditions.

| Category | Specific Risk | Typical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Mode | Perinatal (mother‑to‑child) | Highest chronicity rate (90% become chronic) |

| Unprotected sexual contact | Elevated risk, especially with multiple partners | |

| Injection drug use | Shares needles → direct blood exposure | |

| Geography | Living in East Asia, Sub‑Saharan Africa, Pacific Islands | Endemic regions where HBV prevalence >5% |

| Medical Factors | Co‑infection with HIV or hepatitis C | Immune suppression accelerates chronic infection |

| Family History | Having a parent with chronic hepatitis B | Increased likelihood of perinatal transmission |

Understanding these factors helps health‑care providers target screening and vaccination efforts where they matter most.

How Is Chronic Hepatitis B Diagnosed?

Diagnosis relies on a combination of serologic markers and imaging. The most informative tests include:

- HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) - persists for ≥6months in chronic infection.

- HBeAg (hepatitis B e‑antigen) - indicates high viral replication.

- HBV DNA quantification - measures the amount of virus in the blood.

- ALT and AST levels - gauge liver inflammation.

- Liver ultrasound or elastography - assess fibrosis or early cirrhosis.

Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend regular monitoring every six to twelve months for most patients.

Treatment Options and When to Start

Not everyone with chronic hepatitis B needs medication. Treatment decisions hinge on viral load, liver enzyme levels, and the presence of liver damage. The two main classes of antiviral therapy are:

- Nucleos(t)ide analogues such as tenofovir and entecavir - suppress viral replication with a low resistance profile.

- Interferon‑α - an injectable that boosts the immune response but carries more side effects.

Patients with high HBV DNA (>20,000IU/mL), elevated ALT, or evidence of fibrosis usually start a nucleos(t)ide analogue. The goal is to keep the virus undetectable, lower ALT, and prevent progression to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Preventing New Infections

The most effective shield against hepatitis B is vaccination. The standard three‑dose schedule provides >95% protection for healthy adults. For newborns, a birth‑dose within 24hours is critical-especially in endemic regions.

Additional preventive measures include:

- Safe sex practices (condom use, limiting partners).

- Never sharing needles or tattoo equipment.

- Screening blood products and organ donors.

- Educating pregnant women about antiviral therapy to reduce mother‑to‑child transmission.

When people combine vaccination with these behavioral strategies, the incidence of new chronic infections drops dramatically.

Related Liver Complications

Chronic hepatitis B is a stepping stone to more serious liver disease. Two conditions commonly linked are:

| Complication | Typical Timeline | Key Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 10-30years of uncontrolled infection | Elevated fibrosis score on elastography |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Often after cirrhosis develops | New liver nodule on imaging, AFP rise |

Regular surveillance, especially ultrasound every six months for high‑risk patients, catches cancer early when curative treatments are possible.

Living With Chronic Hepatitis B

Most people lead normal lives with proper medical care. Key habits that make a difference:

- Adhere to antiviral medication schedules.

- Avoid excessive alcohol, which compounds liver injury.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and lean protein.

- Stay up‑to‑date with vaccinations for flu and hepatitis A.

- Engage in regular check‑ups; early detection of fibrosis changes management.

Support groups and online forums also provide emotional backing and practical tips for managing appointments and medication side effects.

Next Steps for Readers

If you think you might be at risk, talk to a health‑care provider about a simple blood test for HBsAg. For those already diagnosed, ask about the latest antiviral options and liver‑health monitoring plans. Finally, share reliable vaccine information with friends and family-prevention starts with awareness.

Key Takeaway

chronic hepatitis B is a silent yet serious liver infection that can be controlled with early detection, effective antiviral therapy, and vaccination. Knowing the symptoms, causes, and risk factors empowers you to protect your liver and your loved ones.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can chronic hepatitis B be cured?

A true cure-complete eradication of HBV cccDNA-doesn’t exist yet. However, modern antivirals can suppress the virus to undetectable levels, halting liver damage and reducing cancer risk.

How often should I get screened for liver cancer?

If you have cirrhosis or a high viral load, an abdominal ultrasound every six months is recommended. Adding AFP (alpha‑fetoprotein) blood tests improves early detection.

Is the hepatitis B vaccine safe for adults?

Yes. The vaccine uses a non‑infectious protein subunit, so it cannot cause hepatitis B. Adults receive three doses over six months, and immunity lasts at least 20 years for most people.

What lifestyle changes help protect my liver?

Limit alcohol, maintain a healthy weight, avoid illicit drug use, and eat a diet low in saturated fat. Regular exercise improves overall liver metabolism.

Can I transmit hepatitis B to my baby if I’m pregnant?

Yes, mother‑to‑child transmission is the most common route for chronic infection. A birth‑dose vaccine plus antiviral therapy during the third trimester for high‑viral‑load mothers reduces the risk to under 5%.

Do I need to tell my sexual partners about my diagnosis?

Open communication is essential. Using condoms and ensuring partners are vaccinated or have immunity greatly lowers transmission chances.

Andy Jones

Oh, sure, just because you tossed in “HBV” without defining it first, everyone magically knows you mean hepatitis B virus.

Also, “>250million” should have a space: “> 250 million”.

And “silent yet serious” is an oxymoron – silent implies you can’t see it, serious implies you can.

But hey, who am I to ruin your poetic flair? Keep the facts, lose the fluff.

Chris Smith

Nice write‑up but the vaccine isn’t a magic bullet.

Leonard Greenhall

The article correctly emphasizes that chronic infection often remains asymptomatic, yet it could elaborate on the role of cccDNA in therapeutic resistance. Additionally, the risk stratification based on viral load and ALT thresholds aligns with AASLD guidelines. It would be useful to mention that tenofovir has a higher barrier to resistance compared to older nucleos(t)ide analogues. Finally, a brief note on the significance of HBeAg seroconversion would round out the discussion.

Abigail Brown

Reading this feels like a beacon of hope for anyone grappling with the silent weight of chronic hepatitis B.

It reminds us that early detection can turn a looming nightmare into a manageable condition.

The emphasis on vaccination is a rallying cry for community health.

And the practical lifestyle tips-less alcohol, balanced diet-show that empowerment starts at home.

Let’s spread this knowledge; the more we talk, the fewer shadows the virus can hide in.

Ashley Stauber

Honestly, the “one‑size‑fits‑all” vaccine schedule ignores genetic variability in immune response.

Will Esguerra

It is incumbent upon us, as stewards of public health, to scrutinize the nuanced interplay between viral genomics and host immunity delineated herein.

The exposition of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) furnishes a mechanistic substrate for viral persistence, a point often relegated to peripheral discourse.

Moreover, the delineation of therapeutic thresholds predicated upon HBV DNA quantification underscores the necessity for vigilant monitoring.

While the article commendably enumerates nucleos(t)ide analogues, it omits a comparative analysis of their long‑term renal safety profiles, a consideration of paramount importance in chronic therapy.

In sum, the manuscript provides a robust scaffold upon which clinicians may construct individualized management algorithms, yet it beckons further elaboration on emerging biomarkers such as quantitative HBsAg.

Allison Marruffo

Great summary! I especially appreciate the clear breakdown of risk factors and the reminder to stay current with vaccinations. Keeping a balanced diet and regular check‑ups really does make a difference, and it’s encouraging to see that emphasized. Let’s keep sharing reliable information.

Ian Frith

For those navigating chronic hepatitis B, consider integrating liver elastography into routine follow‑up; it offers a non‑invasive glimpse into fibrosis progression. Additionally, emerging data suggest that finite courses of pegylated interferon may achieve functional cure in a subset of patients with favorable baseline characteristics. When counseling patients, frame antiviral therapy as a long‑term partnership rather than a fleeting prescription, emphasizing adherence to prevent resistance. Finally, patient support groups can alleviate the psychological burden often associated with chronic disease.

Beauty & Nail Care dublin2

Wow, this article is sooo helpful!! 😍 I never knwoed that HBV can be hidden in your liver for years. The part about vaccine being 95% effective is mind‑blowing 🤯. Also, dont forget to get your pregnant mommies vaccinated 🍼. Keep the info comin, it's lifeline stuff!! 👍

Oliver Harvey

Did you really spell “hepatitis” as “hepatites” in the heading? 🙄

Ben Poulson

The exposition is thorough; however, one might contend that the section on lifestyle modifications would benefit from citations to peer‑reviewed studies. Additionally, the temporal frames for surveillance imaging could be refined to reflect recent guideline updates. Overall, a commendable effort.

Tara Phillips

Let us champion vigilance and proactive health measures, for in the realm of chronic hepatitis B, prevention truly is the most potent remedy.

Derrick Blount

First, let us acknowledge: the virus-HBV-is a DNA virus;; it integrates-well, not truly integrates-but persists as cccDNA; second, the vaccine-administered in three doses-provides >95% protection; third, regular monitoring-ALT, HBV DNA, elastography-is indispensable; finally, adherence-to antivirals such as tenofovir or entecavir-is the cornerstone of long‑term management.

Anna Graf

HBV is a bad virus. You need a shot and medicine.

Jarrod Benson

Okay folks, let’s break this down step by step because chronic hepatitis B isn’t just some random buzzword you toss into a conversation and forget about; it’s a relentless adversary that silently builds up damage over years, and that’s why early detection through routine blood work can be a total game‑changer. First, you’ve got the vaccine, three shots over six months, and that alone can stop most people from ever getting infected. Then, if you’re already infected, you have antivirals like tenofovir and entecavir, which keep the virus in check and protect your liver from turning into scar tissue. And don’t overlook lifestyle-cutting booze, eating greens, staying active-they all help your liver repair itself. Bottom line: stay informed, get tested, and stay on top of your health plan, because knowledge is literally power when it comes to beating this virus.

tom tatomi

The so‑called “universal vaccination” strategy ignores regional genetic resistance patterns.

Tom Haymes

While the article does an excellent job outlining the clinical aspects, let’s also remember the psychosocial impact of a chronic diagnosis. Providing patients with counseling resources can improve adherence to therapy and overall quality of life.

Scott Kohler

It is astonishing that the mainstream narrative continues to extol tenofovir and entecavir as if they were infallible panaceas. In reality, years of clandestine clinical trials have revealed subtle nephrotoxic signals that are conveniently buried beneath layers of regulatory jargon. Moreover, the purported 95% vaccine efficacy is derived from studies funded by conglomerates with vested interests in pharmaceutical monopolies. One cannot ignore the quiet elimination of alternative herbal interventions that have shown promise in attenuating hepatic inflammation. The omission of cccDNA‑targeted therapies from the guideline discourse is a deliberate strategy to maintain market exclusivity. Simultaneously, the WHO’s estimates of 250 million chronic carriers conveniently downplay the potential for engineered viral strains. It is no coincidence that the same agencies endorsing universal vaccination also lobby for increased patent protections. The emphasis on “regular monitoring” every six months serves to entrench a profitable surveillance industry. Patients are subtly coerced into lifelong dependence on costly antivirals, a model that benefits a handful of multinational corporations. The lack of transparent data sharing erodes public trust and fuels speculation about hidden side effects. While the article praises adherence, it neglects to mention the socioeconomic barriers that render compliance impossible for many. The narrative also sidesteps the ethical controversy surrounding maternal antiviral therapy during pregnancy. All of these omissions suggest a coordinated effort to control the discourse surrounding hepatitis B. Consequently, informed citizens deserve to scrutinize the source of these recommendations rather than accept them blindly. In short, the veneer of scientific objectivity masks an agenda that prioritizes profit over genuine public health outcomes.

Brittany McGuigan

While you spin conspiracies, the United States remains committed to eradicating hepatitis B through widespread immunization programs.