Theophylline levels aren’t just another lab number. For patients using this old-school bronchodilator, getting the level right can mean the difference between breathing easily and ending up in the ER with a seizure or dangerous heart rhythm. Even though newer asthma and COPD medications have taken center stage, theophylline still holds a place-especially when other treatments fail. But here’s the catch: it’s not a drug you can just prescribe and forget. The window between helping and harming is razor-thin, and without careful monitoring, things can go wrong fast.

What Makes Theophylline So Dangerous?

Theophylline works by relaxing airway muscles and reducing lung inflammation. It’s been around since the 1930s, and while it’s not the first choice anymore, it’s still used in stubborn cases where inhaled steroids and long-acting bronchodilators don’t cut it. But unlike most drugs, you can’t guess the right dose based on weight or age alone. The safe range? Between 10 and 20 mg/L. Go below 10, and it barely works. Go above 20, and you’re flirting with serious trouble-vomiting, tremors, irregular heartbeat, even seizures.

What makes this worse is how unpredictable the body is with theophylline. One person might need 300 mg a day to hit 15 mg/L. Another, with the same weight and condition, might hit 25 mg/L on 200 mg. Why? Because the drug’s metabolism is messy. It’s broken down by the liver, and that process changes depending on what else is going on in the body.

Why NTI Monitoring Isn’t Optional

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like theophylline have a tiny gap between effectiveness and danger. There’s no room for error. That’s why checking blood levels isn’t just good practice-it’s mandatory. The American Thoracic Society says it plainly: don’t use theophylline unless you’re ready to monitor levels regularly.

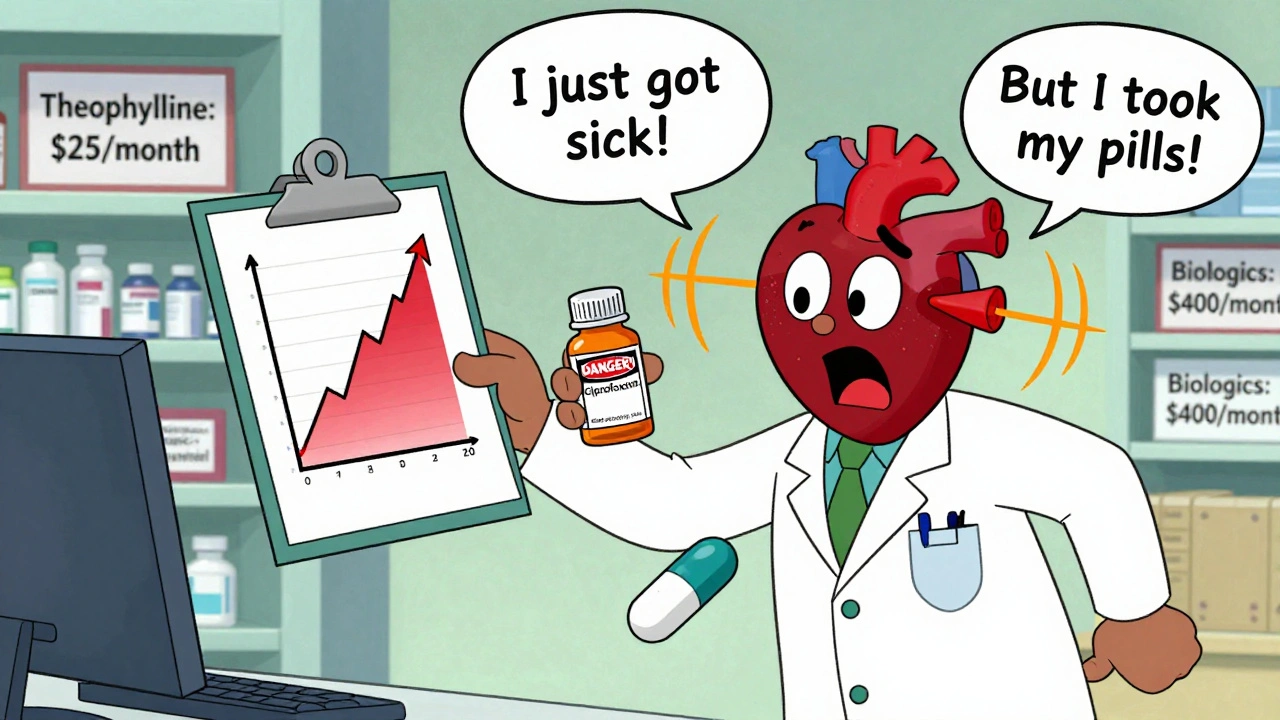

Many doctors still think, “They’re taking their pills, so it must be fine.” But that’s a trap. A patient could be taking their dose exactly as prescribed and still end up toxic. Why? Because of interactions. Antibiotics like ciprofloxacin or erythromycin can spike theophylline levels by 50-100%. Even over-the-counter drugs like cimetidine (for heartburn) can do the same. On the flip side, smoking boosts metabolism-so a patient who quits smoking might suddenly see their levels rise dangerously high without any dose change.

One 2023 case report told the story of a 68-year-old man with COPD. He was stable on 400 mg daily. Then he got a urinary tract infection and was prescribed ciprofloxacin. Three days later, he collapsed with ventricular tachycardia. His theophylline level? 28 mg/L-well into toxic territory. He survived, but only because doctors caught it in time.

Who Needs Monitoring Most?

Not everyone needs the same frequency. But some groups are at much higher risk:

- Patients over 60: Liver function slows with age. Monitor every 3-6 months.

- People with heart failure or liver disease: These conditions cut theophylline clearance by half or more. Check every 1-3 months.

- Pregnant women: Clearance drops 30-50% in the third trimester. Monthly checks are needed.

- Smokers who quit: Levels can rise quickly. Check within 1-2 weeks after quitting.

- Anyone starting or stopping antibiotics, antifungals, or seizure meds: These can dramatically alter levels. Test before and after.

Even if a patient seems stable, skipping a check because “they’ve been fine for years” is a gamble. Theophylline doesn’t care about history-it only cares about what’s happening right now.

When and How to Test

Timing matters. You can’t just draw blood anytime. For immediate-release tablets, you need to test right before the next dose-that’s the trough level, the lowest point in the cycle. For extended-release versions, wait 4-6 hours after taking the pill. Testing too soon gives a false high; testing too late gives a false low.

It takes about 5 days for the drug to reach steady state after starting or changing the dose. So don’t test before then. After that, stable patients can go 6-12 months between checks. But if anything changes-new meds, illness, lifestyle shift-test immediately.

And don’t forget: IV theophylline is even trickier. The infusion rate can’t exceed 17 mg/hour unless levels are known to be below 10 mg/L. Mixing it with dextrose solutions? Big no. It can cause clumping or hemolysis.

More Than Just a Number

Looking at the theophylline level alone isn’t enough. You need to connect it to the patient’s symptoms and other lab values.

- Heart rate: Over 100 bpm? Could be early toxicity.

- Potassium: Theophylline can cause low potassium, especially if the patient is also on albuterol or diuretics. Low potassium worsens heart rhythm risks.

- Neurological signs: Headache, insomnia, jitteriness-these are red flags before seizures kick in.

- Respiratory status: If someone’s breathing worse despite high levels, it’s not working-and toxicity may be masking the problem.

One 2022 study showed that hospitals using a structured monitoring protocol cut adverse events by 78%. That’s not luck. That’s discipline.

The Cost of Skipping Monitoring

Every year in the U.S., about 1,500 people end up in emergency rooms because of theophylline toxicity. About 10% of those cases are fatal. The National Health Service reports that 15% of these events happen because doses weren’t adjusted for liver problems. Another 22% are from unmonitored drug interactions-especially with common antibiotics.

And here’s the irony: theophylline is cheap. Generic versions cost $15-$30 a month. Compare that to biologic asthma drugs that run $200-$400 a month. So cost isn’t the reason to skip monitoring. It’s the opposite-the low price makes it tempting to use without proper oversight. But that’s a false economy. One ER visit for toxicity can cost 10 times more than a year’s worth of monitoring.

What’s Next for Theophylline Monitoring?

There’s hope on the horizon. Companies like TheraTest Diagnostics and PharmChek Solutions are developing handheld devices that can measure theophylline levels from a drop of blood in under five minutes. These point-of-care tests are in phase 2 trials and could change everything-especially in rural areas or nursing homes where sending blood to a lab takes days.

But until those tools are widely available and proven, the standard stays the same: serum level testing. The American College of Chest Physicians made that clear in 2024. No shortcuts. No exceptions.

Even if you think your patient is fine, even if they’ve been on the same dose for years, even if they’re not complaining-check the level. Because theophylline doesn’t warn you. It doesn’t give you a chance to react. It just flips a switch. And once it does, it’s too late.

The bottom line? If you’re prescribing theophylline, you’re signing up for lifelong monitoring. No exceptions. No excuses. The narrow therapeutic index isn’t a suggestion. It’s a rule written in blood.

How often should theophylline levels be checked?

For stable patients on a consistent dose, check every 6-12 months. But more frequent monitoring is needed for high-risk groups: every 3-6 months for patients over 60, every 1-3 months for those with heart or liver disease, and monthly during the third trimester of pregnancy. Always test after starting or stopping any new medication, after quitting smoking, or if symptoms of toxicity appear.

What happens if theophylline levels are too high?

Levels above 20 mg/L increase the risk of side effects. Between 20-30 mg/L, patients may experience nausea, vomiting, tremors, and rapid heartbeat. Above 30 mg/L, serious toxicity kicks in: seizures, irregular heart rhythms (like ventricular tachycardia), and even cardiac arrest. Levels over 25 mg/L are considered life-threatening and require immediate medical intervention.

Can you take theophylline without monitoring?

No. Major medical societies, including the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society, state that theophylline should never be prescribed without a plan for regular therapeutic drug monitoring. Even low doses can become toxic due to unpredictable metabolism, drug interactions, or changes in health status. Skipping monitoring is dangerous and considered below the standard of care.

What drugs interact with theophylline?

Many common drugs affect theophylline levels. Enzyme inhibitors like ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, allopurinol, and cimetidine can raise levels by 50-100%. Enzyme inducers like carbamazepine, rifampin, and St. John’s Wort can lower levels by 30-60%. Even smoking and alcohol change how the body processes the drug. Always review all medications and lifestyle factors before prescribing or adjusting theophylline.

Why is theophylline still used if it’s so risky?

It’s still used because it works-especially in severe asthma or COPD that doesn’t respond to standard inhalers. It has anti-inflammatory effects beyond just opening airways, including restoring HDAC2 function in severe disease. It’s also extremely affordable compared to biologics. For patients in resource-limited settings or those who can’t tolerate newer drugs, it remains a vital option-when monitored properly.

Do point-of-care theophylline tests exist yet?

Not yet for routine use. Several companies are developing handheld devices that can measure theophylline from a fingerstick in under five minutes, and they’re in phase 2 clinical trials. But until these are FDA-approved and proven accurate in real-world settings, traditional blood tests drawn and sent to a lab remain the only accepted method for monitoring.

Eddie Bennett

Theophylline is one of those drugs that feels like it belongs in a museum but somehow still survives in clinics. I’ve seen patients on it for decades, and honestly, the monitoring is the only thing keeping them alive. One guy I knew quit smoking, didn’t tell his doctor, and ended up in the ER with a heart rhythm that looked like a seizure on the monitor. No one checks levels anymore unless they’re forced to. That’s the problem.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

Exactly. And it’s not just about the numbers-it’s about connecting the dots. I had a patient last month with a theophylline level of 24 mg/L, no symptoms, no complaints. But her potassium was 2.9, and she’d been on albuterol nebs for a week. She was one arrhythmia away from code blue. We adjusted her dose, added KCl, and rechecked in 48 hours. That’s the standard. Not guesswork. Not hope.

Jack Appleby

It’s absurd that we still use this 1930s relic when we have biologics with half the risk profile. Theophylline’s pharmacokinetics are a nightmare-unpredictable, interaction-prone, and metabolized by a liver that’s often already compromised in COPD patients. If you’re prescribing this without a dedicated TDM protocol, you’re not practicing medicine-you’re playing Russian roulette with a loaded gun labeled ‘generic.’

Kristi Pope

I get why people hate it but also why it sticks around. It’s cheap. It works when nothing else does. I had a veteran who couldn’t afford his inhalers but could afford theophylline. He was stable for years-until he got antibiotics for a sinus infection and didn’t tell anyone. We caught it before the seizure. That’s why monitoring isn’t bureaucracy-it’s lifeline. Don’t ditch the drug. Ditch the laziness.

Doris Lee

My grandma’s on it. She’s 78, has COPD, and checks her levels every 4 months like clockwork. She doesn’t skip doses, doesn’t take random OTC stuff, and always tells her doctor when she starts a new med. That’s the kind of patient we need more of. Not the ones who think ‘I’ve been fine for 10 years’ means it’s fine.

Courtney Blake

Ugh. Another post about theophylline. Like we don’t have 10,000 other drugs that are actually safe. This is why American medicine is broken-obsessed with ancient, dangerous relics because they’re cheap. Meanwhile, real innovation gets buried under red tape. Just ban the damn thing. Let people use biologics or die. No more half-measures.

Lisa Stringfellow

Everyone’s acting like this is some groundbreaking revelation. Newsflash: theophylline toxicity has been a known problem since the 80s. If you’re still surprised by this, maybe you shouldn’t be prescribing anything. I’ve seen this exact case three times in my last rotation. The pattern? Doctor forgets to check levels. Patient gets sick. Everyone acts shocked. It’s not a mystery. It’s negligence dressed up as ‘clinical judgment.’

Kaitlynn nail

Life’s a balance. Theophylline’s a relic. But sometimes relics still breathe. The real villain isn’t the drug-it’s the system that lets people forget to check.

Frank Nouwens

As a clinical pharmacist with over 22 years of experience in respiratory therapeutics, I must emphasize that the therapeutic drug monitoring protocol outlined in this post aligns precisely with the 2024 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines. The emphasis on trough levels, steady-state timing, and interaction screening is not merely best practice-it is the standard of care. Any deviation constitutes a breach of professional obligation. I commend the author for this rigorous and evidence-based summary.