Depression and Heart Disease Risk Calculator

This tool estimates your risk of developing heart disease based on depression severity and common lifestyle factors. Results are for educational purposes only and do not replace professional medical advice.

When you hear the words depression is a mood disorder that causes persistent sadness, loss of interest, and a range of physical symptoms. It’s more than a mental health issue-it can reach deep into your body, especially the heart. Heart disease refers to conditions that affect the heart’s ability to pump blood, including coronary artery disease and heart failure. Research shows a two‑way street: depression raises the chance of heart problems, and heart disease can trigger depressive episodes.

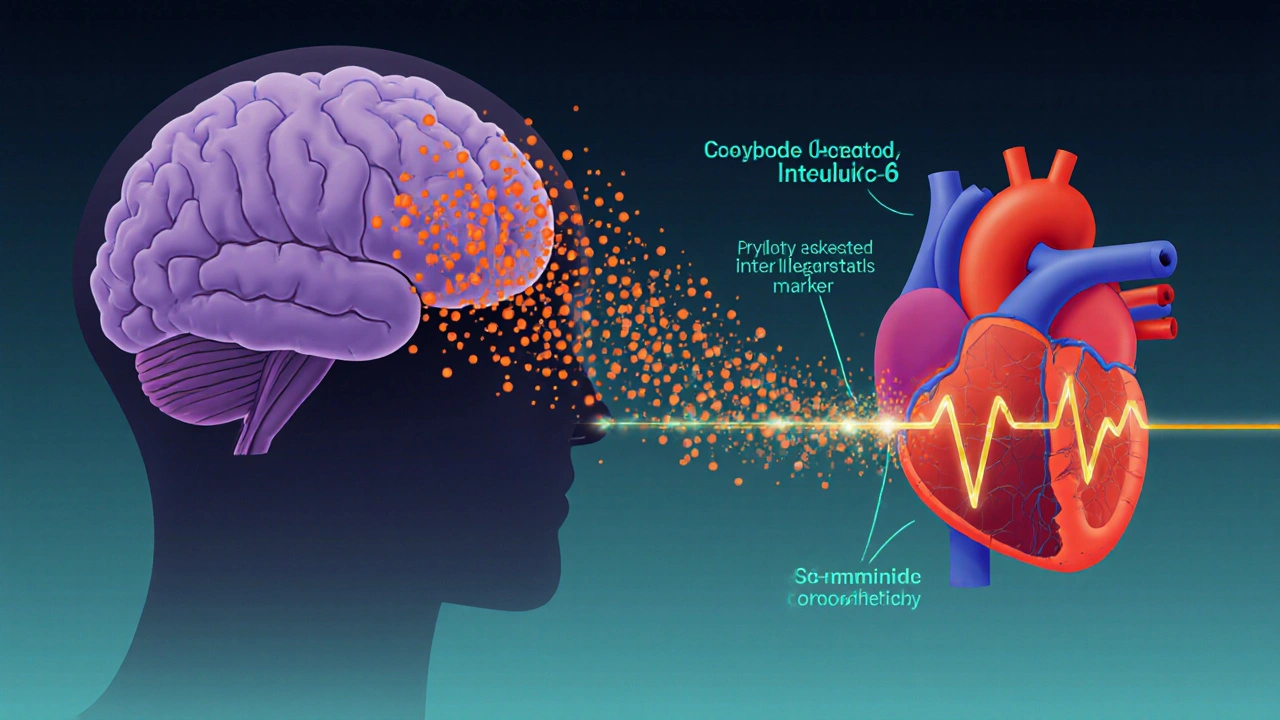

Why Depression Impacts the Heart

Several biological pathways turn a low mood into a cardiac threat:

- Stress hormones: Chronic depression pushes up cortisol levels, which raise blood pressure and promote plaque buildup.

- Inflammation spikes: Depressed individuals often have higher C‑reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin‑6, both linked to arterial damage.

- Autonomic dysfunction: The balance between sympathetic (fight‑or‑flight) and parasympathetic (rest‑and‑digest) systems tilts toward sympathetic dominance, causing irregular heartbeats.

These changes don’t happen overnight. Over years, they erode blood vessels, raise cholesterol, and make clot formation more likely.

What the Numbers Say

Large‑scale studies back up the biology. The 2023 Global Mental Health and Cardiology Survey followed 150,000 adults for ten years. Participants with a clinical diagnosis of depression had a 1.8‑fold higher risk of heart attacks compared to non‑depressed peers, even after adjusting for smoking, diet, and exercise.

Another meta‑analysis of 27 cohort studies (2022) found that every point increase on the PHQ‑9 depression scale corresponded to a 5% rise in cardiovascular mortality. In plain language: the more severe the depression, the steeper the heart risk curve.

Shared Lifestyle Triggers

Depression and heart disease often share habits that worsen both conditions. Think of a vicious loop:

- Low mood reduces motivation → fewer workouts.

- Physical inactivity leads to weight gain and higher blood pressure.

- Weight gain fuels depressive thoughts, creating more inactivity.

Key overlapping factors include:

- Smoking - nicotine spikes heart rate and deepens depressive feelings.

- Excessive alcohol - depresses the central nervous system and raises triglycerides.

- Poor diet - high‑sugar, low‑fiber meals spike blood sugar and trigger mood swings.

- Sleep disruption - both conditions thrive on chronic insomnia.

Do Antidepressants Harm the Heart?

Medication can be a double‑edged sword. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are first‑line for depression and have a fairly neutral cardiac profile. Some studies even suggest they lower platelet aggregation, possibly reducing clot risk.

However, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and certain monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can raise heart rate and prolong the QT interval, especially in older adults with existing heart disease. It’s essential to discuss cardiac history with a prescribing doctor, who may favor an SSRI or a newer serotonin‑norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) that has less impact on heart rhythm.

Managing Both Conditions: A Practical Checklist

| Action | Why It Helps | How to Implement |

|---|---|---|

| Regular aerobic exercise | Boosts serotonin, improves blood pressure | Start with 20min brisk walking, 3×/week |

| Balanced Mediterranean‑style diet | Reduces inflammation, stabilizes mood | Eat fish, nuts, olive oil, plenty of veggies |

| Mind‑body practices | Lowers cortisol, eases anxiety | Try 10min guided breathing daily |

| Smoking cessation | Improves oxygen delivery, cuts depressive triggers | Use nicotine patches or counseling services |

| Medication review | Avoid drugs that stress the heart | Ask your doctor about SSRI vs. TCA options |

| Sleep hygiene | Restores hormonal balance | Keep a consistent bedtime, limit screens |

Following this checklist doesn’t guarantee a cure, but it dramatically cuts the odds of a heart event and can lift mood scores within weeks.

Warning Signs: When to Seek Help

Both conditions can hide until they turn serious. Watch for these red flags:

- Chest discomfort or pressure that lasts longer than a few minutes.

- Sudden, unexplained shortness of breath.

- New, intense feelings of hopelessness or thoughts of self‑harm.

- Rapid heartbeat at rest (palpitations) combined with anxiety.

- Persistent fatigue that doesn’t improve with sleep.

If any of these appear, call emergency services or visit the nearest urgent care. Early intervention saves lives.

Bottom Line

The link between depression and heart disease is real, backed by biology, big data, and everyday observations. Treating one without the other leaves a hidden danger. By tackling stress hormones, inflammation, and lifestyle habits together, you protect both mind and heart.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can depression cause a heart attack?

Yes. Research shows people with clinical depression have up to an 80% higher chance of experiencing a heart attack, largely due to chronic inflammation and elevated cortisol.

Do all antidepressants increase heart risk?

Not all. SSRIs are generally safe for the heart, while older drugs like TCAs can affect heart rhythm. Always discuss your cardiac history with the prescriber.

Is exercise safe if I’m depressed?

Physical activity is one of the most effective ways to lift mood and lower heart risk. Start slowly-20 minutes of walking three times a week-and gradually increase intensity.

How quickly can lifestyle changes affect heart risk?

Positive changes can show benefits within weeks. Blood pressure may drop in 2‑4 weeks, and mood scores often improve after 4‑6 weeks of consistent exercise and diet improvements.

Should I get screened for heart disease if I have depression?

Yes. A baseline check of blood pressure, cholesterol, and a resting ECG can catch early signs. Discuss screening frequency with your primary care doctor.

ADAMA ZAMPOU

When we examine the psychophysiological pathways, the link between chronic depressive states and autonomic imbalance becomes unmistakable. Elevated cortisol and inflammatory markers associated with depression can accelerate atherosclerotic processes. Moreover, depressive individuals often adopt sedentary lifestyles, which compounds cardiovascular risk. The calculator you shared captures some of these factors, yet it omits psychosocial stressors that are equally consequential. Integrating behavioural therapy outcomes could refine risk stratification. Ultimately, addressing mental health is not ancillary but central to heart disease prevention.

Liam McDonald

I appreciate the effort put into the tool it offers a concise overview of how mental health intersects with cardiovascular risk it also reminds us that lifestyle modifications matter greatly

Adam Khan

The pervasive use of simplistic risk calculators betrays a deeper epistemic laziness in our public health discourse. First, the algorithmic reduction of PHQ‑9 scores to a fixed integer ignores the nuanced psychoneuroimmunological cascades that modulate endothelial function. Second, the model assumes a linear covariance between activity days and myocardial risk, a premise that is statistically untenable outside controlled cohort studies. Third, the binary smoker flag fails to capture dose‑response curves for nicotine exposure, thereby skewing the resultant risk index. Fourth, alcohol consumption is treated as a monolithic variable, disregarding the differential impact of binge versus moderate intake on atrial remodeling. Fifth, the absence of socioeconomic covariates renders the tool culturally myopic, especially when applied to heterogeneous populations across North America. Sixth, the proprietary weighting scheme appears to privilege American dietary norms while marginalising alternative nutritional paradigms. Seventh, there is no adjustment for genetic predisposition, a glaring omission given the heritability of both depression and coronary artery disease. Eighth, the interface presents risk categories in colour‑coded boxes that may inadvertently trigger anxiety, counterproductively elevating cortisol levels. Ninth, the lack of a disclaimer about potential algorithmic bias undermines informed consent. Tenth, the tool’s reliance on self‑reported data introduces recall bias that can inflate or deflate risk estimates arbitrarily. Eleventh, the static risk thresholds ignore longitudinal trajectories, which are essential for prognostic accuracy. Twelfth, the model does not incorporate recent findings on gut‑brain axis dysbiosis as a modifiable factor. Thirteenth, by presenting the output as a definitive “risk level,” the calculator discards the probabilistic nature of epidemiological inference. Fourteenth, the user experience design lacks accessibility features for visually impaired individuals, contrary to inclusive design principles. Fifteenth, the underlying code appears to be a truncated copy‑paste from outdated cardiology textbooks, suggesting a lack of scholarly rigor. In sum, while the calculator might serve as a pedagogical toy, it should not be conflated with a clinical decision‑support system, especially not in a landscape where public health policy is often weaponised against minority communities.

rishabh ostwal

It is a moral imperative to recognize that the suffering of a depressed mind does not exist in a vacuum; it reverberates through the vasculature with a cruelty that should alarm any conscientious citizen. One cannot ethically endorse a tool that merely quantifies risk without simultaneously urging systemic interventions that address the root causes of both mental anguish and cardiac decay. To remain silent is to tacitly endorse a society that values numbers over lives.

Kristen Woods

Yo, this calculator looks like a cheap spreadsheet you’d see in a high school bio class-so oversimplified it makes my head spin!!! The whole "add 3 points if PHQ‑9 ≥10" thing is laughable, as if mental health can be reduced to a few points on a screen. It totally ignores the fact that socio‑economic stressors and cultural stigma play a massive role in both depression and heart disease. And what about the fact that the risk thresholds are as arbitrary as a Monday morning meeting agenda??? This is just a gimmick that pretends to be science while actually feeding misinformation. Get a real model or get out.

Carlos A Colón

Wow, thanks for putting this out there-nothing like a shiny calculator to remind us that our hearts and minds are secretly best friends. It’s almost funny how a few clicks can highlight something we already know: caring for our mental health is a cardio‑saving move. If only more people would actually use this instead of just scrolling past it, maybe we’d see fewer broken hearts, both figuratively and literally. Keep it up, you’re doing a solid service.

Aurora Morealis

Interesting tool.

Sara Blanchard

This is a helpful resource for anyone looking to understand the intertwined nature of mental health and cardiovascular health. It encourages open conversations about topics that are often kept separate, fostering a more holistic view of wellbeing. Sharing tools like this can empower communities to take proactive steps, especially when cultural stigma makes such discussions difficult.

Anthony Palmowski

Seriously??!!! This calculator is a joke!!! The way it lumps complex psychosocial variables into a single number is not just lazy, it's dangerous!!! It’s as if someone threw a bunch of buzzwords together and called it science!!! Anyone with a brain knows that health metrics can’t be reduced to a three‑point add‑on!!! Stop peddling half‑baked tools!!!

Jillian Rooney

It’s pretty clear that this kind of oversimplified risk scoring only works for the "average" American who fits the narrow demographic assumptions baked into the algorithm. For us who live in more diverse socio‑cultural environments, the calculator feels like a one‑size‑fits‑none approach. I wish the developers would actually consult a broader set of data before claiming universal applicability.

Krishna Sirdar

I think it’s great that we’re getting tools that bring mental health into the conversation about heart disease. Simple changes like walking a few extra days a week or seeking therapy can make a big difference. Let’s keep sharing resources like this and remind each other to look after both mind and body.

Courtney Payton

One could argue that reducing human experience to a line on a screen is a philosophical oversimplification of the self. Yet, perhaps this is a necessary abstraction to motivate action, even if it feels a bit hollow. If the calculator nudges someone toward a healthier habit, maybe the trade‑off is acceptable, albeit imperfect.